In a legal career that has spanned more than 30 years, High Court Justice Michael Kirby has emerged as one of Australia’s most prominent and controversial judges. Known in legal circles as ‘The Great Dissenter’, Kirby is regarded by many as the champion of the minorities. Often aligning his decisions with public perceptions of justice and citing international human rights principles in his judgments, the man known for colourful public appearances has injected humanity and compassion into a system renowned for an unemotional, exacting brand of conservatism.

Michael Romei

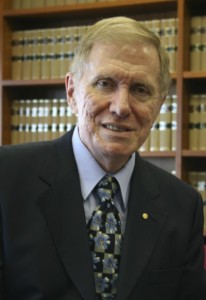

With such a reputation preceding him, it is surprising to discover that in person Kirby is somewhat reserved. Sitting in his Sydney Chambers, his rather chaotic office overshadowed by a magnificent city view, Kirby, 69, takes time providing his responses. But while each word is perfectly framed and anecdotes are inserted seamlessly, there is something about the rehearsed nature of the encounter that is possibly more revealing than words themselves.

Indeed, in a rare case of the judge being the one questioned, the result is a cautious and perhaps even wary manner. Kirby is like a fortress, allowing outsiders to stare in awe at the exterior façade, but stopping short of providing access to the core of his being. While this could easily be attributed to his occupation, it is perhaps more likely to find its origins in Kirby’s past relationships with the Australian media, a history that he is all too aware of – and possibly resents – as he approaches retirement.

Indeed, in a rare case of the judge being the one questioned, the result is a cautious and perhaps even wary manner. Kirby is like a fortress, allowing outsiders to stare in awe at the exterior façade, but stopping short of providing access to the core of his being. While this could easily be attributed to his occupation, it is perhaps more likely to find its origins in Kirby’s past relationships with the Australian media, a history that he is all too aware of – and possibly resents – as he approaches retirement.

Now Australia’s longest serving judge, Kirby is nearing the end of his tenure, with the compulsory retirement age for High Court Justices set at 70. As such, questions are inevitably raised about Kirby’s legacy. Will he be remembered for his brilliant mind, pioneering approach to justice and service to the Australian community? Or will he be resigned to a footnote in the public consciousness as the High Court’s first openly gay justice, punctuated by a scandal involving NSW senator Bill Heffernan?

It is perhaps this concern over his legacy that influences his presentation to the media. This becomes evident during the interview when, asked about whether he believes there a double standard when it comes to the amount of scrutiny on his life because of his homosexuality, Kirby deviates from the script to justify his public attention.

“I think there’s a degree of extra scrutiny but … you have by your questions made a lot of emphasis on my sexuality, but I don’t think that is the reason or the sole reason for attention. I’ve been in the public eye for 30 years. I’ve been involved in a lot of high profile activities, and public scrutiny is part of the reality of a democratic society, and if you don’t like the heat, you shouldn’t enter the kitchen.”

Kirby’s unease is only furthered when the incident for which he is perhaps best known to the general public is raised. In 2002 senator Bill Heffernan produced documents, later revealed to be forgeries, suggesting that Kirby trawled for rent boys in Sydney’s Kings Cross. It was a period of intense media scrutiny, one that threatened to end, and may have defined, his illustrious career.

“I reacted with outrage [over the allegations] and the senator withdrew them and apologised when it was demonstrated that they were totally false,” says Kirby. “Having been brought up in a Christian tradition, I accepted his apology and forgot about it. But no one in [the media] wants to do so.”

“I don’t want to be labelled after my 30 years of service for the people of Australia with that incident in my life. I want to be remembered for my work for law reform, for justice, for minorities, for all people, and it’s important to say that and put things in perspective.”

Kirby was born into a working class family of Irish descent and grew up in Concord with his sister and two brothers. Describing his upbringing as “rather ordinary”, Kirby believes that his background has heavily influenced his values and approach to decision making.

“I went to public schools, and I think that gives you a sense of contact with the values of all Australians. That’s because the children in the schools were of people of different backgrounds, different religions or no religion, different ethnicity, different parental wealth. That is a good thing in a democracy for a judge to grow up with, because it means you can empathise with everybody, not just the big end of town.”

Upon completing high school, Kirby went on to study law at the University of Sydney. He was admitted to the NSW Bar in 1967, and in 1983 he became the youngest man appointed to the Federal Court of Australia, after which he served as president of the NSW Court of Appeal. In 1996 he was selected to become the 40th Justice of the High Court.

During his time on the bench, Kirby has often been criticised for allowing his personal beliefs to impact his decision-making. While acknowledging this is the case, Kirby says it is an unavoidable consequence that is common to all judges, and those making such criticisms show a lack of understanding of the judicial system.

“Every judge’s personal feelings affect their judgments. Judges have to interpret the constitution, which is a very brief document. Judges have to interpret and give effect to laws made by parliament, which are expressed in language of great generality. Judges have to find and declare the common law in completely new circumstances.”

“This is not automatic pilot business. This is the matter of determining value-loaded decisions. I’m just more open about it.”

At the same time as acknowledging this personal element to the judicial process, Kirby stops short of embracing the term ‘judicial activist.’ He believes the label is problematic as “it tends to be used by conservative people as code language for people who make decisions improperly.” He does admit, however, that there is a degree of activism in the law, which is something that should be embraced where necessary.

“For hundreds of years judges in our legal tradition have been expressing and developing the law. No one calls that activism. That is simply the process of the way the common law evolves,” Kirby says.

“For hundreds of years judges in our legal tradition have been expressing and developing the law. No one calls that activism. That is simply the process of the way the common law evolves,” Kirby says.

“If I see injustice I don’t just sit there and accept it. I see whether within the law I can cure the injustice according to law. That’s in effect what I swore I would do when I became a judge. Law is about upholding the rules but also upholding justices.”

It is perhaps for these reasons that Kirby has dissented from his notoriously less-liberal colleagues on so many occasions, leaving him with the highest rate of dissent of any Justice in the High Court’s history. He is candid in admitting that his relationship with the six other Justices is one of professionalism rather than love, but despite being seemingly isolated on the bench Kirby says he has never felt any external pressure to follow suit.

“It’s much easier for you if you do. All you have to do then is send around a piece of paper saying “I agree” and you don’t have to write anything. You can just swim in the pool and have another gin and tonic on the weekend. So that’s a sort of indirect pressure, but I don’t think it’s a correct pressure and it’s one to which I never succumb.”

While in the past outgoing High Court Justices have voiced preferences for their replacements, this is something the usually outspoken Kirby refrains from doing. Though he acknowledges that this is an unusual position, he believes it is the correct one, though does admit he would like to see another liberal thinker appointed.

“I don’t believe judges should be involved in the appointment of their successors, otherwise clone-like reproductions occur, and that’s not how the world develops creatively. The societies in history that have been most creative have been polyglot societies made up of people of different ethnicities and backgrounds and attitudes.”

“A great court is made up of a diversity of opinion and values. I think we can do with a few ‘capital-L’, or ‘small-l’ liberals on the High Court, and I would hope that is what will happen.”

Kirby refrains from discussing his sexuality in any real depth, preferring to direct the interview along his own lines, but this is not the only topic he shies away from. From gay marriage – an issue he has discussed on many occasions – to the national apology to the stolen generation, Kirby is adamant, “there are some topics a judge shouldn’t comment on.”

Eventually, with mounting dissatisfaction over Kirby’s reluctance to discuss Australian current affairs, he is asked whether he looks forward to being able to speak more openly when he retires.

“I haven’t felt frustrated. I haven’t tossed and turned on my bed at night when I’ve been subject to rules. When you’re a judge you know there are rules and you stick to the rules.”

Of his plans for the future, Kirby says he looks forward to a “quiet old retirement.” But having stated in the past that “my life is work”, Kirby’s quip that he expects to be an ordinary retiree appears to be just that. Having worked on a number of boards and committees, and with a strong interest in human rights, it is expected that Kirby will further pursue these interests. But when pressed to elaborate, he provides the ambiguous, but by now thoroughly expected response.

“I’m so busy surviving from day to day that I don’t worry about what will happen in the future. Something will turn up. It always has in my life.”