‘Over in LA, all the crews call you ‘Sir’ … I just don’t think it’s right. I’m just one of the many cogs flying around a planetary gear which is the director’ He started his career on a relative’s farm in Queensland before discovering a passion for photography. Today, the Oscar winner for Best Cinematography is one of the most in-demand men in his field in Hollywood and, while his job takes him around the world and back, his home and heart will always be in Sydney.

Several years ago, sitting in a Hollywood agent’s office, John Seale quietly suggested that his film credit be changed from “director of photography” to “cinematography by”. Across the desk, the agent met him with a stunned expression. Used to fanning egos, contesting billings and generally demanding “more” in a town known for its competitive self promotion and desire for advancement, this was a step backwards. “Do you know thousands have died to keep director of photography?” the agent exclaimed, in reference to past attempts to have the title removed when the roles of director and cinematographer became separate.“You take that away now and you’ll be blacklisted for the rest of your life!”

Several years ago, sitting in a Hollywood agent’s office, John Seale quietly suggested that his film credit be changed from “director of photography” to “cinematography by”. Across the desk, the agent met him with a stunned expression. Used to fanning egos, contesting billings and generally demanding “more” in a town known for its competitive self promotion and desire for advancement, this was a step backwards. “Do you know thousands have died to keep director of photography?” the agent exclaimed, in reference to past attempts to have the title removed when the roles of director and cinematographer became separate.“You take that away now and you’ll be blacklisted for the rest of your life!”

Intrigued, the Oscar winner for The English Patient asked if it’s really that serious. The reply was immediate. “It’s not far off !” Today, sitting outside a marina in the secluded suburb of Bayview, John, 65, laughs heartily as he recalls the incident.

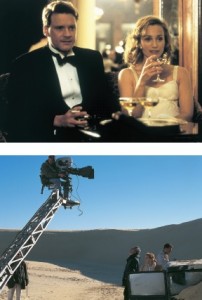

It’s a story that encompasses his personality. Despite working on some of the world’s biggest films, including Cold Mountain, Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone, The Talented Mr Ripley and Spanglish, he is a man completely void of ego or pretension. “The agent I had then was aghast,” John says in his straight-talking manner. “[In America] it’s a very old boys’ club that really tries to keep the ‘respect’ of that position … Over there all the crews call you sir, which

I hate. I just don’t think it’s right. I think that you’re just one of the many cogs flying around a planetary gear which is the director.” John hunches over the wooden table and seems oblivious to the strong wind whipping his face. He wears a jacket he got while filming The Perfect Storm, which comes in handy as the rain becomes steadily stronger, a large umbrella swaying precariously above. When asked to try and explain his profession, he pauses. “I have a lot of people say ‘what the heck do you do?’” he eventually replies, smiling with a slightly rough charm. “The simplicity of it is, we photograph the movie.”

It is this that has made John one of the most sought-after names in Hollywood for the past 20 years, with director Anthony Minghella describing him as one of the greatest cinematographers that’s ever been.

But John says it has been a long journey to where he is today. Born in Queensland, then moving to Sydney as an infant, John’s school career was characterised by uncertainty about the future. Leaving without any idea of what to do, he began working at a printing office for a short period before deciding to go back to Queensland to work as a jackaroo on a relative’s farm. Unusually, it was there that John, working long and intensely physical hours, laid the foundations for his film career.

“I took with me a little eight millimetre camera and just started filming,” he says. “And the more I did that, the more I began to think, could I ever get a job that would take me ’round the world to far-flung corners where people can’t go, wont go, can’t afford to go, or have never been. And go there with a camera and film it so people can enjoy that area.”

After 18 months, John decided he was not suited to the physical and mental strain required working on the farm. He then sold his Land Rover and hitchhiked back to Sydney, where he worked as a cameraman at the ABC for seven years. It was there that he realised how much he enjoyed working with actors.

“I suddenly through my experiences at the ABC began to work with actors, and I couldn’t believe how exciting it was. I remember going to Broken Hill to shoot a TV drama and taking the young Jacki Weaver out there. And boy was that exciting, because we were in the outback, which I love, and we had actors who were creating a whole new storyline to the camera. And so that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.” It was while at the ABC, learning on the job and attending what he describes as “the school of hard knocks”, that John came to grasp the discipline of photography. “I learnt to do things properly,” he says.

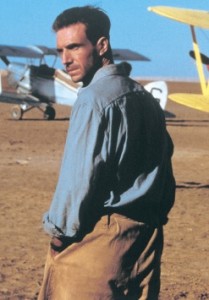

“ And I think that’s held me in fantastically good stead in an American industry where time is big money. It’s not just money, it’s big money.” John’s first taste of the American industry and all its politics came in 1984 when he was invited by the Australian director Peter Weir to travel overseas and film Witness, starring Harrison Ford. John describes that as his “big break”, namely because it resulted in his first Academy Award nomination.

And I think that’s held me in fantastically good stead in an American industry where time is big money. It’s not just money, it’s big money.” John’s first taste of the American industry and all its politics came in 1984 when he was invited by the Australian director Peter Weir to travel overseas and film Witness, starring Harrison Ford. John describes that as his “big break”, namely because it resulted in his first Academy Award nomination.

“The adage in America,” he explains, “is that once you’re nominated, you never have to worry about work again. Because to them it’s like being knighted – it’s almost royalty! So from that day on, that movie cemented an awful lot of my future.” The pleasure of gaining international recognition was somewhat dampened for several years by the reaction John received from some former co-workers back home. “The Australian Tall Poppy Syndrome hates anyone venturing overseas. It wasn’t good there for a long time. I was actually punched out at a party because I was going overseas, not because I’d been and come back.

“He knocked me down and I fell backwards into a little fountain about six inches deep,” he recalls. “I didn’t spill my beer, which I was very proud of, and I didn’t kill any of the goldfish. But I sat there and I thought, ‘What was that for!’ All I’m doing is being lucky enough to go overseas and help make an American film.” John believes such reactions have lessened in the past decade, with Australian’s becoming more proud of the success of local talent overseas.

Today, he is among a raft of internationally lauded Australian cinematographers, including Dean Semler (Dances With Wolves), Russell Boyd (Master And Commander: The Far Side Of The World), Andrew Lesnie (The Lord Of The Rings) and Dion Beebe (Memoirs Of A Geisha). When asked about the reasons for this success, John doesn’t hesitate in explaining it’s because Australian cameramen are “quick, fast and good”. “Sometimes cinematographers get too precious about their photography and every shot has got to be a Rembrandt,” he explains. “It doesn’t. I think the movie should be a Rembrandt. There could be 555 shots in that movie. If each one’s a Rembrandt, you might have cost the company a lot of money and time setting them up, getting them perfect, waiting for the sun to be exactly right. And that’s not on. They don’t want that. They want cameramen who can make a good-looking movie and not waste time and money.”

“It’s either because of that, or they’re putting something in the beer,” he adds with a laugh. “We all drink enough of it!” While John freely admits that he himself has in the past wanted to shoot sections of films in a beautiful way “which maybe didn’t honour the film”, he also says that over time he has learnt that it is more important to follow the director’s overall vision. “I don’t agree that photography that looks good is best for every movie. I always try to make the photography of the exteriors suit the story.”

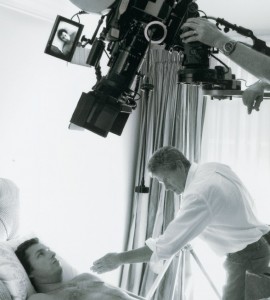

It is for this reason John hopes he won his Oscar for The English Patient in 1997. He says that on the night  he was initially scared to hear his name read aloud, as he was convinced that he would “break the chain of wins” as the blockbuster film steamrolled through almost every category. “I had always vowed over the years that I would never pull out a piece of paper and start reading names, so I didn’t prepare a speech,” he explains.

he was initially scared to hear his name read aloud, as he was convinced that he would “break the chain of wins” as the blockbuster film steamrolled through almost every category. “I had always vowed over the years that I would never pull out a piece of paper and start reading names, so I didn’t prepare a speech,” he explains.

“But during that moment, with all the adrenaline rushing, you can’t think of anything. Names go out the bloody door. I remember the big monitor that comes out of the crowd and begins counting down from 42.

Some of the most vehement criticisms came for John’s Oscar-nominated work in Cold Mountain in 2003. With the film already the subject of a smear campaign for being shot in Romania instead of on American soil, criticisms were mainly levelled at the lighting of Nicole Kidman, rather than the overall style.

Many critics thought she appeared flawless, thereby undermining the believability of her reformed and land-working character during the American Civil War. It is a point John acknowledges as valid, but also one he believes he had little control over. “The bottom line is, she’s an absolutely gorgeous looking woman, and she has looked after herself in more ways than one,” he admits.

“She had an amazing make-up man, and she was flawless … the negatives of today record that.You know, the old adage: the camera never lies.” John also says Nicole was aided by the setting in which the film was shot. “I had a lot of trouble in a funny kind of way with nature, because we shot in the snow in Romania. Now some of the best fill light in the world is coming up from underneath, because it fills in all of the little shadow areas of the face. It simply made her look even better, and people accused me, and make-up, of putting too much highlight under her eyes. But I saw that when we were shooting it.

“I mentioned it to the director [Anthony Minghella], who said ‘Why? She hasn’t got it on.’ And I said it was because of the snow, so he asked if there might be something we could do anything about it. So we actually laid cheap black material on the snow, to try to stop the light bouncing up under her eyes.” With the heavy rain eventually abating, John looks past the armada of sailing boats bobbing gently at their moorings to where streams of light are penetrating through thick clouds, throwing light onto the water. There is no place, he says, he would rather be. “There’s nowhere else in the world as beautiful as Sydney. It’s absolutely magnificent,” he says.

“I mentioned it to the director [Anthony Minghella], who said ‘Why? She hasn’t got it on.’ And I said it was because of the snow, so he asked if there might be something we could do anything about it. So we actually laid cheap black material on the snow, to try to stop the light bouncing up under her eyes.” With the heavy rain eventually abating, John looks past the armada of sailing boats bobbing gently at their moorings to where streams of light are penetrating through thick clouds, throwing light onto the water. There is no place, he says, he would rather be. “There’s nowhere else in the world as beautiful as Sydney. It’s absolutely magnificent,” he says.

“And to tear yourself away from that and go and live in Romania for eight or nine months is hard. Even LA is hard. It’s a zoo of a town, and I love it while I have to be there, but boy I can’t wait to get out either, and get back to this.” Despite being in high demand, John says he now wants to reduce the frequency of his film work in order to spend more time at home with family. Grinning widely as he admits he always plans to retire after every movie, this seems unlikely to occur anytime soon. “I’m physically quite capable of going on. I hope mentally I’m capable of going on. “As long as people will have me,” he adds, in typically modest fashion.