‘The Olympic gold medal, that’s the high of all highs. It’s an environment of everything you’ve always strived for. Pride, joy, and relief … a lot of relief’ The former Olympic swimmer opens up about his youth as an avid athlete, his rise to gold-medal fame, his 13-year stint at the top of L’Oréal Paris, and how he finally managed to rediscover that twinkle in his eye.

Training to become a champion in a Bankstown pool during the early 1950s, a then very young and unknown John Konrads was already getting a taste of the competitive challenges that define an athlete’s career. “It was a zoo!” he recalls. “First of all, we didn’t have lane space, so the reason we swam early in the morning was because that was when the public weren’t around.”

Training to become a champion in a Bankstown pool during the early 1950s, a then very young and unknown John Konrads was already getting a taste of the competitive challenges that define an athlete’s career. “It was a zoo!” he recalls. “First of all, we didn’t have lane space, so the reason we swam early in the morning was because that was when the public weren’t around.”

“After school,” he continues, “and particularly during holiday periods, we literally had to plough our way through [the pool]. We just grabbed the centre two lanes and played water polo with kids’ heads as we swam over them, until they finally kept out of the way!”

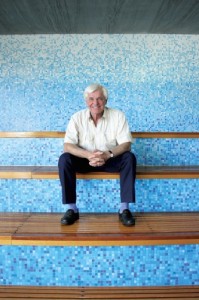

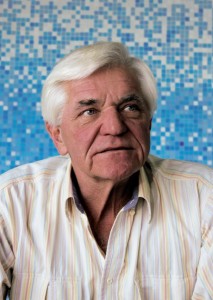

It was a stark contrast to where the Olympic swimming legend finds himself today. As one of the lease-holders of the spectacular $40 million Cook & Phillip Park – an aquatic centre in the heart of Sydney – the now 65-year-old John is surrounded by state-of-the-art facilities that would have the swimmers of yesteryear drowning in envy. However, despite the tough conditions, John says he always loved swimming.

“It was a question of relativity,” he calmly explains, now sporting a healthy shock of white hair. “No-one had it easy. A lot of kids trained in sea pools and other indoor pools that were quite a bit worse.” As it was, John considered himself very lucky to be able to swim at all, attributing his eventual emergence as a swimming powerhouse to little more than a fortunate series of little coincidences.

Born in Latvia, he moved to Australia with his family in 1949. John had the good fortune of staying in the Uranquinty Migrant Hostel, which was the only one in NSW that had a swimming pool. It was there that John taught himself to swim before his family moved to a house in Pennant Hills in Sydney’s north-west. With their rather rare backyard pool, John was able to further his swimming before eventually settling in Revesby and attending the local primary school. “When I went to school there,” he explains, “I asked [other students] whether there were any school races, and there weren’t, they were only for the high schools. All they had was rugby and cricket.

“But then one kid piped up and he said to go speak to Mr Talbot in class 4C, as he was an apprentice coach down at the Bankstown Baths.” “That was Don Talbot, of course, who went on to be arguably one of the greatest coaches in the world. So Don one day took us down to Bankstown to join the club and the rest was really a snowball [effect]. Club races, western suburbs championships, Australian championships, and the Commonwealth and Olympic Games.”

Having attended the 1956 Melbourne Olympics as an alternate and missing out on a competitive swim,

John’s career flourished in the following years. In 1958, at the age of just 15, he astonished the world by breaking every world freestyle record from the 200-metre men’s to the 1500m. In the lead up to the 1960 Rome Olympics John broke a stunning total of 14 individual world records. Along with his record-breaking sister, Ilsa, they were dubbed the “Konrads twins” by the media, who fawned upon them at unprecedented levels. Don Talbot would later say the attention they demanded was twice as much as Ian Thorpe in his heyday.

“Well, maybe not twice as much,” John responds when asked of Don’s comments. “You can’t forget that the media was smaller in those days. “TV had only just started, [there were no] Who Weekly magazines and muck-breaking newspapers … but I think, relatively speaking, it’s probably correct.” John went into the 1960 Olympic Games with very highexpectations and chose to concentrate on two individual events – the 400m and 1500m freestyle. Overwhelmed by pressure in the 400m, John ended up with the bronze medal in the event he was world record holder of. He responded days later in what is now regarded as “Australia’s race”: the 1500m.

“The Olympic gold medal, that’s the high of all highs,” he says. “I don’t think anyone has clear memories about [the moment they win]. It’s just an environment of everything that you’ve always strived for, and you can’t put it into words. It’s pride, joy, relief. Actually, a lot of it is relief – [you think] thank Christ it’s over!” Following his performance in Rome, John accepted a scholarship to attend the University of Southern California (USC). While during the days of amateur sport this seemed like a natural progression, having been preceded at USC by swimmers Murray Rose and John Hendricks, John is candid in admitting this essentially signalled the end of his swimming career.

“You’ve got to understand that in those days USC was a rich kid’s school, the movie stars’ kids’ school … and when I got there it was party time,” he says. “That’s where I plateaued … In one way I suppose if I’d stayed in Australia my career would have been more successful.” After only qualifying for a relay spot at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, John retired.

“I was egotistical,” he admits. “And it wasn’t good ego, it was bad ego … But Ilsa and I, neither of us liked competing really. We set all our world records at times when we didn’t have any people breathing down our necks.”

Afraid of becoming what he describes as “an old poolside man”, the intelligent and charismatic John moved to Paris to work at an exclusive country club.

It was there he met his future wife, Mikki, and joined L’Oréal Paris, who offered him the role as managing director of their company in Australia and New Zealand. It was a position John accepted and, in 1973, at the age of 30, he moved to Melbourne. In hindsight, John believes it was perhaps a case of too much, too soon. “I never worked my way up through the ranks,” he says. “I was 30 years old when I was MD and I lacked the strength of character and experience of having had some tough calls.” Despite his inexperience, John managed to stay at L’Oréal Paris for 13 years before becoming general manager of marketing at Ansett and attempting to start his own consultancy company. However, it was during these corporate years John began to suffer from a form of depression known as Bipolar II Disorder, which is characterised by frequent extreme highs and lows.

This severely impacted his work and personal life, but it wasn’t until 2001 that he was diagnosed. “I was not a voluntary seeker of help,” he says. “Too proud – I’ve been through this before! I’ve had tough times before! Pull your socks up, get your act together. And it was Professor Gordon Parker [Executive Director of the Black Dog Institute] who at a party one night came up to me and said he saw the lights go out of my eyes.”

This severely impacted his work and personal life, but it wasn’t until 2001 that he was diagnosed. “I was not a voluntary seeker of help,” he says. “Too proud – I’ve been through this before! I’ve had tough times before! Pull your socks up, get your act together. And it was Professor Gordon Parker [Executive Director of the Black Dog Institute] who at a party one night came up to me and said he saw the lights go out of my eyes.”

Part of the reason John believes it took him so long to own up to the problem and seek help was his “big boys don’t cry” kind of upbringing, and the stigma attached to depression. Because of his experience, he now works closely with the Black Dog Institute.

After a long period away from the pool and life as an athlete, John is enjoying a late-life swimming resurgence. “Life today is very gratifying,” he says, with his trademark smile and sparkling gaze. “Not always easy, often terrific, often very difficult, but the gratifying part is that when it is difficult, I’m self-aware … Through life’s experience you learn, and I think I’m just a wiser person. With wisdom comes acceptance of many difficulties, which increases your chances of solving them. And that’s a nice feeling.”

1 comment for “John Konrads”