Ken Done lives on the Lower North Shore in his home along the cliffs above Chinaman’s Beach. Here, in his luscious garden overlooking the ocean, he can think, be inspired and, figuratively speaking – as much of his surroundings are man-made – be at one with nature.

It’s a stunning day and sunlight is bouncing off the ocean. Ken gives his time and attention generously. Sitting back in a rustic white gazebo overlooking the beach, he talks with refreshing openness. When describing what drew him to the area, the artist speaks carefully and confidently – proof his answer is clear and genuine. It’s in the pale azure of the ocean, he explains. It’s in the laughter of children drifting up to his home at the top of the cliff, the trilling of parakeets and the chattering of magpies that make their homes in the trees around his property.

It’s a stunning day and sunlight is bouncing off the ocean. Ken gives his time and attention generously. Sitting back in a rustic white gazebo overlooking the beach, he talks with refreshing openness. When describing what drew him to the area, the artist speaks carefully and confidently – proof his answer is clear and genuine. It’s in the pale azure of the ocean, he explains. It’s in the laughter of children drifting up to his home at the top of the cliff, the trilling of parakeets and the chattering of magpies that make their homes in the trees around his property.

“I’ve travelled extensively throughout the world and there is, to my knowledge, no other city and no other suburb that has the same kind of feelings as the Lower North Shore. If you’re very lucky, as I am, to live on a waterfront … on Chinaman’s Beach, it’s really a wonderful place to be.”

Ken is an iconic Australian artist known for his bold and vibrant paintings who’s had immense success both worldwide and at home. He pioneered “wearable art”, placing his images on everything from clothing to homewares under the Done Design label and, in 1992, his achievements gained him an Order of Australia for services to art, design and tourism.

“When you decide you want to be a painter … it’s a singular exercise, you simply decide you will make a mark on something … it’s caveman

stuff,” he explains. “The fact that I make a mark on something and it might end up on a poster for sale in New York or on swimwear for sale in Europe – that’s the time in which we live. But what I do is make marks on things.” The view from the artist’s studio explains much of his inspiration.

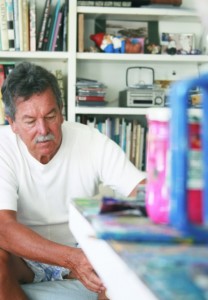

A wall-to-wall window opens up to a picture-perfect beach against a rugged headland.The room is pleasantly crowded with canvasses at all stages of completion. Ken picks up a yellow-dipped brush to put the finishing touches on one of his works. A workbench littered with crayons, pencils and pots and tubes of paint occupies the centre of the room.

crowded with canvasses at all stages of completion. Ken picks up a yellow-dipped brush to put the finishing touches on one of his works. A workbench littered with crayons, pencils and pots and tubes of paint occupies the centre of the room.

One wall is dedicated to his vast collection of books. Opposite, dozens of paint-splattered plastic spades are hung like artwork. Ken explains that he picks them up on the beach, but “only when the children leave them behind, of course,” and puts them to use as palettes. The natural beauty of his surroundings is so striking it should be shared and, in a sense, it is. Looking out from the studio, aficionados could decipher aspects of his paintings on the landscape. The little shack down by the water? It’s in many of his paintings and designs, merrily peeking out at the ocean, watching the tide rise and fall.

The buff, browned, beach bodies and multicoloured beach umbrellas? You’ll find them in Beach Dreaming and Sunday 1982. Ken moved to Sydney from the town of Maclean on the North Coast, where he spent his untroubled childhood running wild and free. “It was, as far as I was concerned, the most idyllic childhood a boy could have. There was no homework, no computers, no television – you just rode your bike, went fishing and mucked around.”

It was in childhood that Ken’s love for art began. “All kids are artists. To be an artist is the easiest thing in the world – to be a good one is very hard. It’s amazing that all of us start with the ability to draw and the absolute confidence we can do it with. Then, somehow, as we get a little older, some people stop doing it, and others trickle on and continue to do it.” Perhaps the country air immunised Ken from the arrogance so often linked with fame. It was certainly in the country his aversion to technology was born. In fact, Ken jokes, becoming an artist was the only path for him because he was so bad at many other things.

“I’m a very stupid person in lots of other areas. I have absolutely no mechanical skills at all. I don’t own a computer. I struggle with mobile phones. I’m always impressed by people who have any kind of technical abilities. But myself, I’m still struggling with the complexities of a can opener. I’m not really interested in anything other than painting.”

“I’m a very stupid person in lots of other areas. I have absolutely no mechanical skills at all. I don’t own a computer. I struggle with mobile phones. I’m always impressed by people who have any kind of technical abilities. But myself, I’m still struggling with the complexities of a can opener. I’m not really interested in anything other than painting.”

He is modest about his talents – this sophisticated, worldly man is, in fact, good at a great number of things. Ken had his first exhibition at the age of 40 because, until then, he was busy with a career in advertising. Coming out of art school, Ken was snatched up by an advertising agency.

“[They] offered me a job at 28 and so – Bang! – I went to them. For the first few years of my career I was working as an art director and designer.”

Ken left that world behind him when he realised he could not bury his desire to paint. “One day, I was on holidays with Judy [his wife] – we were in Noumea I think – and I was supposed to come back on a Sunday and start work again on a Monday morning.

And on Sunday night I said, ‘Sweetheart, I don’t want to do that any more,’ and so, I walked in Monday morning and I resigned.” It was then a matter of launching himself into the art world. He tells an anecdote about how the idea for wearable art, and his worldwide success, was born. Although he has told this story before, he still speaks fondly, seemingly picturing the scene of that first, fateful day when Australia was introduced to Ken Done.

“I was 40 when I had my first exhibition … one of the drawings on the wall was of Sydney Harbour, a very simple blue and white, so I had

12 T-shirts printed to give to the press when they came to do the interviews. The next day people rang up and asked if they could get some

more. And then Vogue did a little piece on them. In those days, there wasn’t much you could wear that said ‘Listen, I live in Sydney, it’s a really

sophisticated place,’ and, really, it worked from there.” Perhaps because of his vast commercial success, critics often accuse him of bastardising art. Ken is not ruffled and responds assertively. “The time in which we live, it seems to me, you can use art in all kinds of fashion, all kinds of media. Whether it’s film or television or fabric or video clips …

For those people who think art should only be made by starving artists in garrets – well, I’m sorry, they’ve simply missed the point.” Conversation turns to his work as Goodwill Ambassador for the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and, as he

speaks of the dead and dying, his face noticeably darkens. He describes visiting Vietnam and Bhutan, and explains his frustration at people whose passing fancies with sick children do more harm than good. “The worst thing that can happen is [when] people fly in somewhere and they have their photo taken with some starving children and fly out again. I don’t think it’s about that at all.”

It’s difficult to imagine the Ken Done of bright palettes and sunny paintings in the bleak surroundings he  describes. Indeed, these images almost never appear in his work. It’s a decision he consciously makes. “I’ve seen things no one should have to see … but I don’t choose to make paintings about horrific things … television and mass communication do it much more strongly than paintings … Let’s take 9/11. How could you make a painting more frightening than the reality?”

describes. Indeed, these images almost never appear in his work. It’s a decision he consciously makes. “I’ve seen things no one should have to see … but I don’t choose to make paintings about horrific things … television and mass communication do it much more strongly than paintings … Let’s take 9/11. How could you make a painting more frightening than the reality?”

‘All kids are artists. We all start with the ability and absolute confi dence we can do it. To be an artist is easy. But to be a good artist is very hard.’

When asked about his infamous longing for a new Australian flag, he is visibly cheered and his voice is so full of warmth he’s practically

glowing. The vision is simple. Ken Done looks down at the table in that white gazebo in his garden and describes Australia’s future with such self-assuredness he’d have politicians convinced. We will soon become a republic, he believes, and insists that when the time comes we’ll need a unifying symbol to represent Australia as a whole.

He describes at length the style, colours and design he envisages. It can’t be anything exclusionary, he stresses – it must encompass all of us. “The footballers or netballers or hockey girls or rugby players are wearing some combination of the Southern Cross and the kangaroo and I think, in the end, our national colours have to be blue and gold.”

And green? “Our sporting colours can be green and gold,” he continues, “but, unfortunately, when we do green and gold we often get it wrong and it looks like a bloody pineapple salad.”

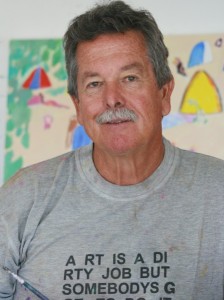

For an artist whose first exhibition was at the age of 40, Ken has achieved so much in a very short period of time. He credits his success to a healthy work ethic. “I don’t believe art is something where you sit around waiting for divine inspiration or smoking dope, or getting drunk. You work at it … you paint 500 pictures. You can’t talk about it – you actually have to do it … there are no shortcuts.”

It is clear that Ken lives by his own motto. The corners of his fingernails are encrusted with paint.

The corners of his fingernails are encrusted with paint.

Not only that, but it’s quite clear those marks have been there for quite some time and that the artist is

in no rush to remove them. To him, those marks and splashes of colour are the badges of his commitment to art – they represent the hours he’s spent tirelessly and passionately at an easel.

Behind the public face, Ken Done is simply an artist indulging his love for art and Australia in a cave of humble creativity, loving what he does and dedicating it to the good he sees. Which seems natural for one who describes his work as making marks on things.